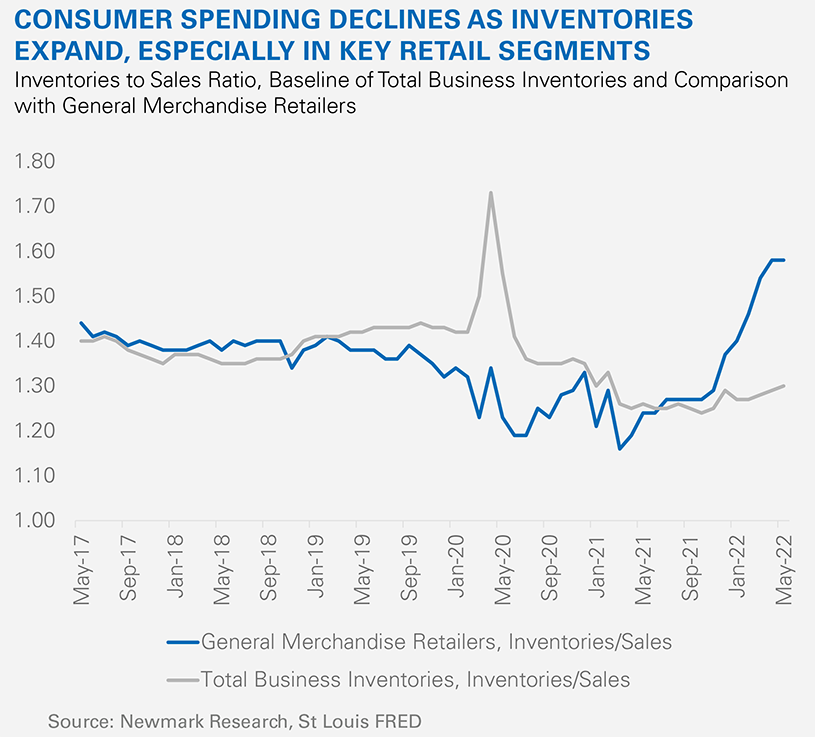

Inventory is building in warehouses across the U.S. as consumer spending changes lanes and downshifts quicker than supply chains can keep up. Persistently high inflation has crimped both real personal expenditures on goods and the number of units per purchase, by 3.6% and 6.0% respectively, year-over-year1. Consumer spending growth has decelerated in real terms. Moreover, the composition is shifting towards services and essential goods that are consumed at a higher rate, and away from bulkier discretionary items like televisions and home-office furnishings. As a result, many retailers are grappling with higher volumes of inventory, slowing demand and record-low warehouse vacancy in which to store accumulating inventory.

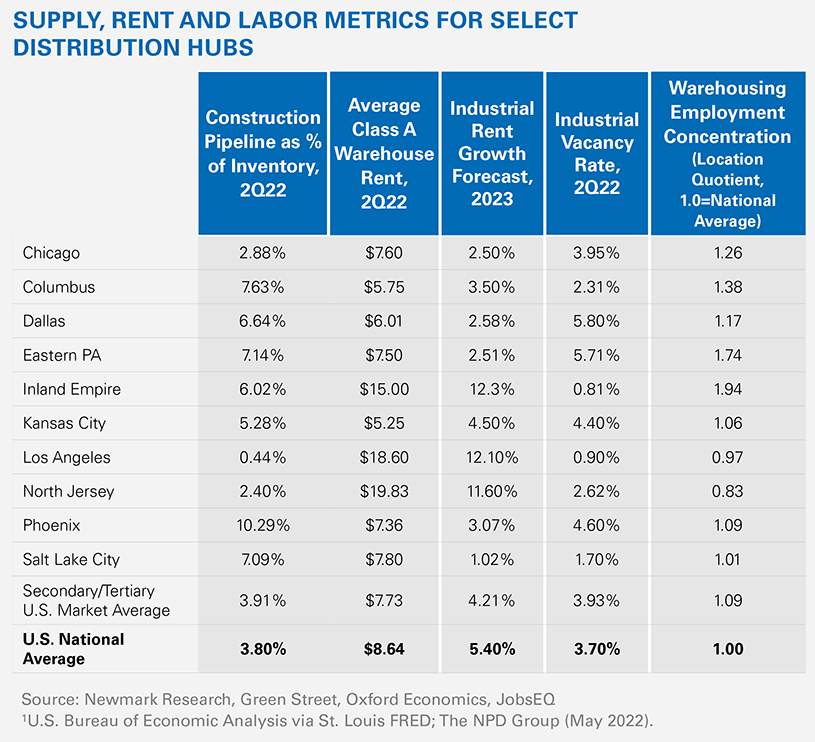

Demand for industrial space is strongly correlated with consumer spending, so as that driver trends back down to pre-pandemic levels of growth, industrial demand will react in turn. Accelerating construction deliveries over the next 12 to 18 months will coincide with a reduction in overall industrial absorption from the all-time heights of 2021. Supply is forecasted to exceed demand by a range of 90 to 120 million square feet in 2023, causing vacancy to increase and rent growth to stabilize as availabilities expand. This macro forecast will have different implications market-to-market, especially as firms consider where to store unwanted inventory at the lowest cost in the short term. Markets well-positioned to reach most of the country’s population in a one or two-day drive cycle with large warehousing labor pools, a significant speculative development pipeline, and lower warehouse occupancy costs with marginal rent growth forecasted, are likely to see a boost in demand from consumer goods and third-party logistics firms looking to displace excess inventory. Whether this yields a short-term boost, or is a structurally sustainable trend for firms strategizing how best to manage non-last mile, “just-in-case” inventory holdings in an unpredictable global economy remains to be seen.